A LITTLE BEFORE 6 p.m. on Tuesday, Liz Ruark started out from the small Worcester County town of Harvard on the 30-mile drive to Kendall Square in Cambridge. Nestled on the floor of the backseat of her Subaru Forester was a Home Goods tote bag whose contents were key to the community’s goal of keeping its schools open while also holding the COVID-19 pandemic at bay.

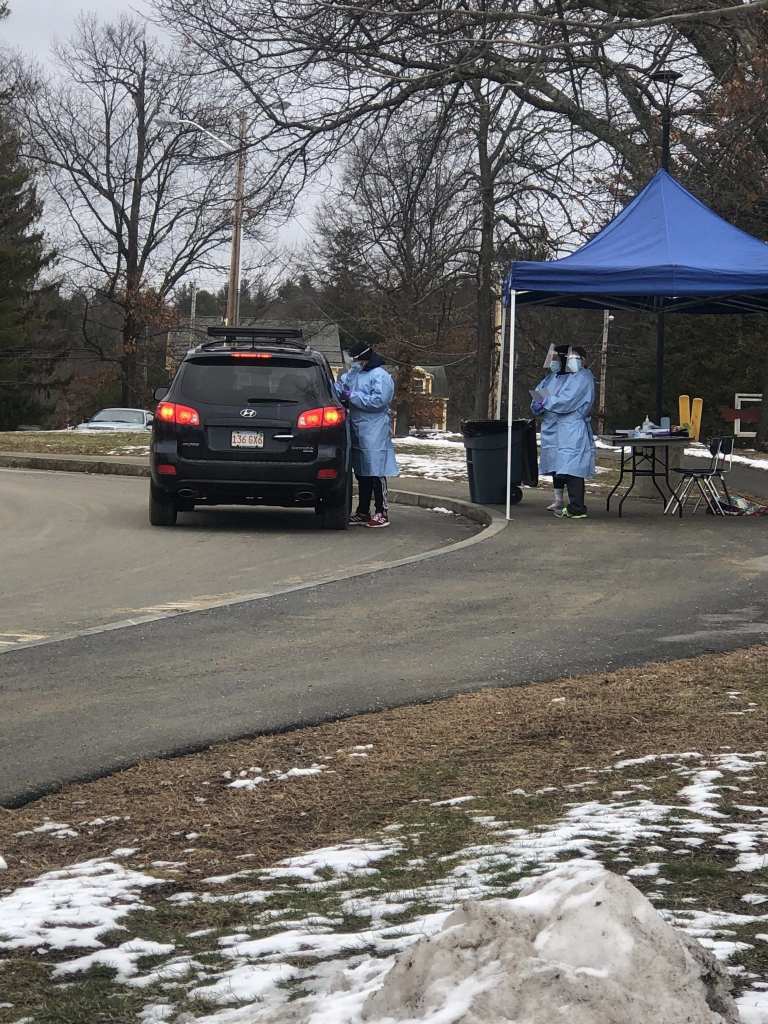

Ruark, a parent of two Harvard public school students, has helped spearhead a five-month effort that culminated in this week’s launch of free weekly coronavirus surveillance testing of all students, teachers, and staff in the rural district. The cargo she was rushing to a Cambridge lab held specimens from the 713 people who showed up throughout the day to have nasal swabs taken at four outdoor testing stations set up outside the town’s combined middle-high school building.

School leaders in the small district serving about 1,000 students say the new testing program, combined with the rollout of a coronavirus vaccine and ongoing mitigation measures like mask-wearing and distancing in schools, offers the best hope yet for at least beginning a return to normalcy 10 months after the pandemic upended public schooling — and virtually every aspect of daily life.

“To keep schools in-person, you have to make sure you’re not bringing asymptomatic cases into the building,” Ruark said.

But the new testing program, which made Harvard one of just a handful of districts in the state to offer regular monitoring of all students and staff, took months of effort, involved private fundraising in a wealthy town, and represented yet another example of the inequities that the pandemic has laid bare.

“It’s setting the haves and have-nots even further apart,” said Linda Dwight, the district’s superintendent, who was supportive of the initiative while also mindful of its unfairness.

That gulf may finally begin to close a little as state officials announced on Friday the launch of a statewide surveillance testing program for all schools.

The Baker administration said it is committing $15 million to $30 million to launch a program that will enable any district in the state to begin weekly surveillance testing of all students and staff. After paying for the six-week start-up phase of the program, state officials said at a State House briefing, districts will be able to use new federal stimulus aid recently approved by Congress to secure ongoing testing services using a single statewide contract that is now being finalized.

“To help our schools bring more kids back, our administration’s education and health experts will make weekly COVID-19 pool testing available to all schools and districts across the Commonwealth within the next month,” Gov. Charlie Baker said.

Baker continued to emphasize that school reopening is safe, saying there is “now an overwhelming body of scientific research that shows that in-person learning can be done without spreading the virus, regardless of the community transmission rates.” But he and top health and education officials at the briefing said the testing program could provide added reassurance to families and teachers who have been concerned about returning to classrooms.

State officials said priority in the new testing program will be given to districts offering in-person or hybrid instruction, but those that are fully remote would also be eligible in order to help them move toward reopening at some level.

Until now, a handful of school districts, including Wellesley, Watertown, and Salem, have launched surveillance testing initiatives, but they have had to fend for themselves in securing testing contracts and funding the effort without a statewide program in place.

Since December, more than 100 districts have begun using rapid coronavirus tests provided by the state, but the Abbott BinaxNOW test is only reliable in testing those showing possible COVID-19 symptoms.

The odyssey faced by school officials and parents trying to stand-up a comprehensive testing program in Harvard, an affluent town that brought plenty of advantages to the effort, underscores how crucial the new state program will be to helping school districts across Massachusetts offer in-person instruction with greater confidence in its safety.

Ruark, who has daughters in the sixth and ninth grade in the Harvard schools, said her training as a veterinarian helped spur her effort, which began in August, to bring regular testing to the schools.

“I’m accustomed to thinking about groups of animals,” she said. “So to me, a school is a herd. As a veterinarian, I want to know who in the herd has a disease. If it can be spread from animal to animal without any symptoms, I can’t stop that spread if I don’t know which animals are sick. The only way to do that is to test them.”

Ruark became convinced that regular surveillance testing of students and school staff — screening all members of the school community, regardless of whether they have exhibited COVID-19 symptoms — was crucial to providing the greatest degree of confidence that it was safe to return to classrooms this fall.

Making that happen proved to be a daunting ordeal.

Financing the testing was the first challenge. The district already committed all of the $300,000 it received in federal CARES Act funds to other mitigation measures to prepare schools for students to return to classrooms. Harvard is employing a hybrid model that divides students into two cohorts, with each group attending in-person classes two days per week.

Although the testing initiative Ruark and another parent started could have solicited donations directly to the school district, in order to have contributions be tax deductible the money has to go through an established 501c3 nonprofit entity.

It took weeks to clear all the hurdles for donations for testing to be handled through the Harvard Schools Trust, an existing nonprofit that provides grants to the town’s two public schools. That created a catch-22 barrier to fundraising. “We couldn’t ask for money when we don’t have a place to put the money,” said Ruark.

Meanwhile, public procurement laws tripped up the first effort to secure a contract to conduct the testing. The district found a company that would handle testing at a price it could afford, but by the time the district was able to issue the required request for proposals, the company had become overwhelmed with testing demands and was not interested in doing the work.

The district finally reached an agreement with CIC Health, a Cambridge start-up that serves as a go-between connecting those in need of testing services with labs that carry out PCR testing, the state-of-art method for detecting coronavirus. The testing is being done a few blocks from CIC Health, at the Broad Institute, a genomics research center jointly operated by Harvard and MIT.

The pooled PCR testing the town is doing — the same model being rolled out under the statewide program — is designed to streamline and reduce the costs of COVID-19 testing. Nasal swabs from 10 individuals are combined and a single test is run on the merged samples. If it is negative, all 10 subjects are deemed free of the virus. Any positive test from a pooled sample is then followed up with individual testing of all 10 individuals to determine who is carrying the virus.

Dwight, the district superintendent, said the weekly testing will provide important peace of mind to school staff. “Teachers came to school every day without knowing whether the students in front of them or their colleagues were positive,” she said.

About 750 of the town’s 1,000 students are signed up for hybrid instruction, while about 250 are attending all classes remotely from home.

Marylou Sudders, Baker’s health and human services secretary, said costs for pooled testing under the contract the state is finalizing will be at least 75 percent lower than those for individual tests. State officials didn’t provide details of the actual cost districts will face.

Harvard is paying $10.50 per individual tested, or $105 for each weekly pooled sample from 10 people. For any pool with a positive result, the charge is $48 for each of the individual 10 follow-up tests that must be carried out.

The pooled testing approach is most cost effective in places like Havard, with low community-level virus rates, since costs rise sharply for each positive pool test. Harvard’s current positivity rate is 3.1 percent, less than half the current statewide 14-day average of 7.7 percent.

Dwight said the district estimates it will need to raise $165,000 to cover the costs of testing for the remainder of the school year.

Ruark said it took dedicated volunteers leading the effort and a town whose families could afford to underwrite testing costs to get the program going in Harvard. “That’s not going to happen in a school system where parents are working two jobs to make ends meet,” she said. “So we’re well that what we’re doing is only happening because we have a certain level of privilege, which is very frustrating.”

Tom Scott, executive director of the Massachusetts Association of School Superintendents, said his members have expressed exactly that frustration at the lack of a statewide plan to help all districts that want to conduct weekly testing.

“It’s just another example of the inequities that we have publicly displayed during this COVID period,” said Scott.

On Wednesday night, Harvard officials got word that two of the 72 pooled tests from the 713 students and teachers who got swabbed on Tuesday came back positive. On Thursday, the 20 people whose samples had been in those two pools had swabs taken again, which were then tested individually. Two came back positive — one student and one teacher, who are now quarantining.

Ruark welcomed Friday’s announcement by state officials. “I’m thrilled that schools throughout the state will be able to take advantage of weekly pooled PCR screening to help increase the safety of their in-person students, faculty, and staff,” she said. “That’s what we want for schools throughout the country: access to consistent, ongoing COVID screening for everyone attending school in person.”

While praising the state effort to broaden access to testing, Ruark said one concern is that the state program plans to use the rapid antigen test on individuals who are part of any initial pool PCR test that comes back positive. She said the rapid test only detects cases in 77 percent of asymptomatic adults and 65 percent of asymptomatic children. “They’re really only accurate for symptomatic adults,” she said.

The state’s largest teachers union hailed today’s development. “After months of unionized educators calling for frequent surveillance testing for COVID-19 in our schools, it is excellent news that the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education is finally setting up a program for all districts that want it,” Merrie Najimy, president of the Massachusetts Teachers Association, said in a statement.

State education commissioner Jeff Riley echoed Baker’s comments that schools that are not sources of COVID spread. But he said the new testing initiative can nonetheless be an important part of the effort to get students back into classrooms.

“This is a voluntary program,” said Riley. “But obviously it’s going to be another tool that people can use to make people feel comfortable about being in school. What I would say is with this and the vaccine that’s on the horizon, better days are ahead.”