THE IMPEACHMENT trial of Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has ended with his acquittal by the Texas Senate. The months-long ordeal has concluded, but the eyes of Texas—and beyond—will probably not stray from Austin soon.

The impeachment of a state officer is a rare bird; only three have occurred in Texas since 1876. Massachusetts has dodged the drama since the removal of Daniel Coakley, a member of the Governor’s Council impeached for “maladministration and misconduct in office” in 1941, amid charges that he sold and otherwise corrupted pardons.

The Paxton trial faced a stiff test to match Coakley’s for color. But the two serve equally to remind us that Texas, Massachusetts, and most states have a “plural” executive branch in which their elected governors do not control all executive officials and sometimes lack power to cut strays from the executive herd. It is the legal independence of these state constitutional officers that requires, in extreme cases, the surgery of impeachment and trial for their removal.

The Texas House voted 121-23 to adopt articles of impeachment against Paxton. Two-thirds of the Senate was required to remove him, though the voting members did not, per a new Senate rule, include his wife, State Sen. Angela Paxton. The articles included allegations of bribery, dereliction of duty, and obstruction of justice. Under the Texas Constitution, his impeachment suspended him from office pending the outcome of his trial. He was the first Texas attorney general ever to be impeached. He was acquitted (no article received more than 14 of the 21 votes needed) and immediately returned to office.

By contrast, Daniel Coakley’s impeachment and removal in 1941 ended his long and notorious career in Massachusetts and Boston politics. The tenor of those turbulent times recalls Ward Just’s portrayal of old Chicago politics: in his novel Jack Gance, Just describes the “City of Broad Shoulders” as “a place where bulls and foxes dine very well, but lambs end up head down on the hook.”

Coakley was born in 1865 in South Boston. As a young man, he worked as a teamster, streetcar conductor, and sportswriter. He later read law in his brother’s law office and passed the bar.

He was elected to the House of Representatives from Cambridge in 1892. He later moved to Brighton and campaigned for John “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, a congressman and later mayor of Boston, and Suffolk County District Attorney Joseph C. Pelletier, a close ally and key player in the downfall of both men to come.

Coakley’s law practice brought him both riches and ruin. His tort and criminal defense practice ended when he was disbarred in 1922 for deceit, malpractice, and gross misconduct, complicit in, among other misdeeds, an extortion scheme involving corrupt district attorneys in Suffolk and Middlesex County (two), all of whom were later removed from office by the Supreme Judicial Court.

Despite his accumulated baggage, Coakley was elected as a member of the Governor’s Council in 1932. He was reelected in 1936, 1938, and 1940. Once seated in the Council, man met moment. The council at that time held wide powers of confirmation over gubernatorial appointments and other key executive decisions, such as pardons. Coakley wielded great influence as a gatekeeper, particularly during the one-term governorship of James Michael Curley from 1935 to 1937. Francis Russell described Coakley’s lucrative business in pardons: “During the Ely and Curley administrations, the quality of Massachusetts mercy grew so strained that more convicts seemed to be leaving prison than entering, not only the misadventured amateurs but well-known professionals. Without the consent of the council, no pardon could be granted, and most of the pardon petitions seemed to emanate from Councilor Coakley.”

One pardon, however, proved one too many. In December 1938, Coakley pushed a pardon for Raymond Patriarca, a Rhode Islander who would later head the underworld for all of New England. Patriarca was pardoned by outgoing Gov. Hurley after serving a mere 84 days of a long sentence for armed robbery. A later investigation revealed that, of the three priests cited in Coakley’s petition for pardon, one—whose name Coakley misspelled—never knew Patriarca, one’s signature had been obtained by fraud, and a third did not exist. This and other evidence of corruption in the pardon process led to Coakley’s impeachment for official misconduct and malfeasance, including the acceptance of bribes, the sale of pardons to felons, and acting “for his own profit and gain in violation of his oath of office.”

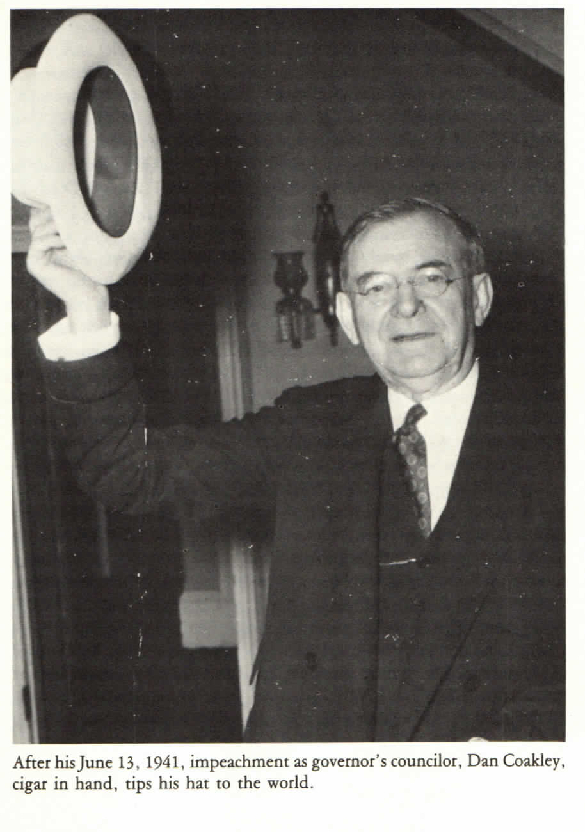

Coakley’s impeachment was the first of a Massachusetts officer since the impeachment of Probate Court Judge James Prescott in 1821. The articles against Coakley were personally prosecuted by Attorney General Robert Bushnell. Coakley’s son, Gael Coakley, defended him. He was removed from office by a vote of 28-10, with several urban Democrats standing by him to the end. By the terms of the Constitution, he was barred from “any office of honor or trust or profit in the Commonwealth.”

Coakley’s rise and fall has earned him chapters in two fine collections of colorful stories about Massachusetts politicians: Russell’s The Knave of Boston and Other Ambiguous Massachusetts Characters (1987), and Gerard O’Neill’s Rogues and Redeemers (2012). Coakley also crosses the stage in scenes in Jack Beatty’s biography of Curley, The Rascal King (1992), Coakley being a contemporary—sometimes an ally, sometimes a foe—of Curley’s. Interest in Coakley shows no sign of waning: he is the subject of a recent biography by Patrick Halley, Dapper Dan: America’s Most Corrupt Politician (2015).

O’Neill paints an unsparing portrait of “Dapper Dan: “To this day, he stands alone as a spectacular political miscreant. . . . But he was also this—a Boston original, defiant in disgrace and truculent amid the ashes. Disbarred. Impeached. Excoriated. No matter. Still standing.” Russell captures Coakley’s checkered career and long fall in a single sentence: “In him the Boston Irish were dealt their knave.”

The sagas of Coakley and Paxson carry lessons beyond the timeless story of ethically challenged officials. The trials also pose an important question of constitutional structure: why are such lengthy, formal proceedings required for the removal of executive officials who rank below the governor of a state? After all, the president of the United States may remove his own attorney general and other executive officers, either at his pleasure or for cause.

Neither Coakley nor Paxton, however, was removable by their governors. In Massachusetts, our Constitution of 1780 created independence for the secretary of state and treasurer, who were at that time elected by joint ballot of the Legislature. The Constitution of 1780 also created an Executive Council, also known as the “Governor’s Council,” comprised of separately elected members whose confirmation of judges is required to this day. Some attribute this division of executive power to John Adams’ revulsion for monarchy — a quite “unitary executive,” with a dash of divine right. In 1855, the Massachusetts Constitution was amended to enlarge the independence for certain executive officers, establishing the popular election by statewide ballot of the attorney general, treasurer, secretary of state, and auditor.

The independence of these officers reflects a deliberate choice not to adopt a more unitary model. In The Federalist No. 70, Alexander Hamilton addressed the question whether the new national government should have a divided (“plural”) or unitary executive branch. Writing in 1787, he strongly endorsed the unitary model. He wrote that “energy in the Executive is a leading character in the definition of good government” and that one of the “ingredients” which constitute “energy in the executive” is unity. He rejected models then used in the states (including Massachusetts) and which divide (to this day) the executive among multiple elected officers, such as governors, treasurers, and attorneys general, and, in some states, comptrollers, insurance and education commissioners, and other officers. He successfully promoted a single, unified executive branch, headed by a president who alone would assume responsibility for executive virtues and vice. A unified executive, Hamilton argued, would promote energy, efficiency, and accountability.

The resulting federal constitution vests in Article II “all” executive authority in the president of the United States. The president nominates all of his cabinet members and may remove them at will. He likewise nominates the members of the so-called “independent” agencies—such as the Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Trade Commission —and may remove them for cause.

Though many state governments resemble the federal government’s structure, they differ in a key respect: executive power is dispersed among a wide range of actors, most of them elected by the people of each state on a statewide ballot, including the attorney general in 43 states. The resulting structure—in Austin and Boston—requires the Legislature to step in to remove certain wayward executive officers. Whether the Massachusetts or Texas governor supports or opposes the impeached officer does not affect the constitutional process of impeachment and trial.

As the recent drama unfolded in Austin, Bostonians of long memory might have compared the Coakley and Paxton trials. Which was the bigger show? Catie Offerman, in her song “Just Don’t Do It in Texas,” sings:

“Just don’t do it in Texas

No, don’t take it that far;

Well, if you’re leaving me lonely,

Leave me that Lone Star.

Yeah, just remember

Everything’s bigger,

And I couldn’t handle a hurt that size,

So don’t do it in Texas,

If you’re saying goodbye . . .”

Who’s to say the Texas attorney general wasn’t channeling Offerman’s tune as he sat in the figurative dock? Many things are bigger in Texas. But those who recall the “Knave of Boston” might smile knowing that, as for political theatre, not everything’s bigger in Texas.

Thomas A. Barnico teaches at Boston College Law School. He was an assistant attorney general in Massachusetts from 1981 to 2010. He is the author of a novel, War College, set in the Vietnam War era.

CommonWealth Voices is sponsored by The Boston Foundation.

The Boston Foundation is deeply committed to civic leadership, and essential to our work is the exchange of informed opinions. We are proud to partner on a platform that engages such a broad range of demographic and ideological viewpoints.